On May 31, 1408, exactly 617 years ago to this day, one of the most ambitious and enigmatic men in Japanese history died suddenly, just as he seemed poised to crown his life’s work with the ultimate prize: imperial sovereignty. That man was Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1358–1408), the third shogun of the Ashikaga bakufu, whose reign marks both the zenith of the Muromachi period and a tantalizing might-have-been in the annals of Japanese power politics.

He was a man of many masks: a ruthless political operator, a master of ceremonial spectacle, a patron of the arts, and a would-be emperor in all but name.

The Boy Shogun

Yoshimitsu became shogun at the age of ten, inheriting a fractured Japan still reeling from the split between the Northern and Southern Courts. But unlike his father and grandfather, Yoshimitsu would not merely reign — he would rule. And unlike many shoguns before and after, he had a vision that reached far beyond military control.

By the time he turned twenty, Yoshimitsu had largely unified the country under his rule. He forced the fractious daimyō into submission, brought the Southern Court to heel, and in 1392 brokered a nominal reunification of the imperial line — a move that many historians still view with suspicion, noting how conveniently it ended the Southern Court’s claims just as the Northern Court, which Yoshimitsu supported, cemented its dominance.

In just a few short years, he had asserted his complete dominance.

Patron of Prestige

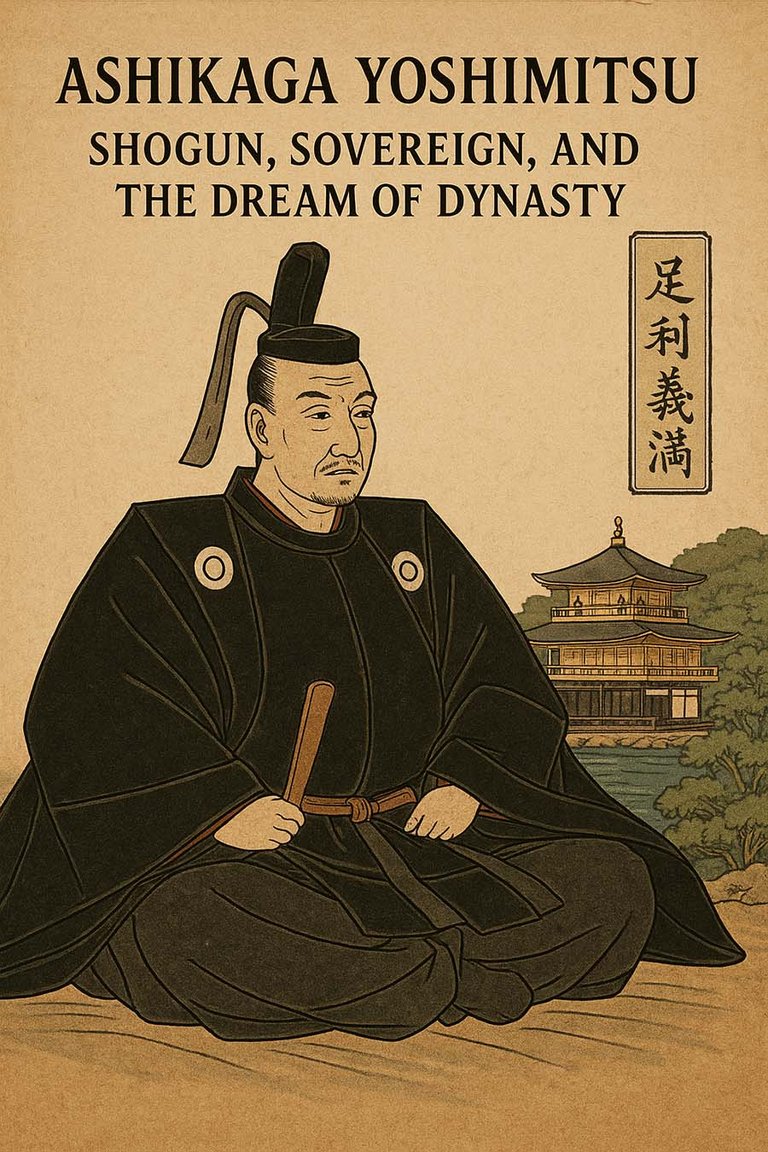

Yoshimitsu didn’t just unify Japan politically — he elevated it culturally. He funded temples, promoted the arts, and built the extravagant Kitayama-dai, a palace complex in the hills of Kyoto whose surviving structure, Kinkaku-ji (the Golden Pavilion), remains one of Japan’s most iconic buildings and to this day one of the most popular attractions for tourists.

He also reëstablished official trade relations with Ming China, going so far as to accept the Chinese emperor’s title for him — “King of Japan” — a move that scandalized later generations but underscored his realpolitik view of power. It wasn’t just about being shogun. It was about appearing to be sovereign on the international stage.

This was the peak of Ashikaga power. Yoshimitsu stood at the height of authority and held a stronger position than any shogun before him — perhaps even more so than Yoritomo, the first shogun, several centuries earlier. He ruled all and was completely untouchable.

Or so it appeared.

Death and a Dynasty Denied?

In his final years, Yoshimitsu took a series of increasingly bold steps to transform his personal authority into something closer to imperial rule.

He retired in name in 1394, handing the title of shogun to his young son Yoshimochi, but remained in power behind the scenes — very much like a cloistered emperor (insei). In the years that followed, he began openly styling himself as something more than a mere shogun. He had already accepted the Ming title of “king”, as mentioned above. He transformed his private residence into a quasi-palatial compound. And by 1408, he was reportedly preparing for a final transformation—being declared Daijō Tennō, a title normally reserved for retired emperors.

The plan was stunning in its implications. The shogun would not only outshine the emperor, but become him, or something like him. Not through usurpation but by ritual absorption — transforming a military dictatorship into a new hereditary dynasty cloaked in imperial ritual. Admittedly, that’s pure speculation on my part. There is no proof that he wanted to start his own dynasty. But why else try to assume the title and position of a retired emperor? The potential ramifications of this move are too hard to ignore.

And then, on May 31, 1408, just as the transformation was underway, Yoshimitsu suddenly died.

He had shown no signs of illness. He was just fifty years old. Rumors swirled: was it natural causes, a stroke, poison, or perhaps divine retribution for overstepping his role? Was he killed by loyalists of the imperial court, or even by factions within his own bakufu who feared the consequences of his overreach?

We’ll never know. But what we do know is this: within days, the plan to elevate him to Daijō Tennō was quietly dropped. His son, Yoshimochi, repudiated his father’s foreign titles and ambitions, cancelled the Chinese tribute missions, and began pulling the Ashikaga back from the brink of imperial transformation.

The moment passed. The dynasty-that-never-was faded into history, leaving only whispers in court documents and the glimmer of gold on the waters of Kinkaku-ji.

Not only did that moment pass — it marked the beginning of the end for his line. The Ashikaga would quietly (and not-so-quietly) fade until they had so little authority or respect that they couldn’t even control Kyoto, much less Japan, and the warlord Nobunaga chased them out of the city.

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu was far more than just another shogun. He was a liminal figure — standing at the edge of two worlds, two forms of government, two systems of legitimacy. One can only wonder what Japan might have looked like had he lived just a few more years, or if his heirs had shared his vision.

Instead, the Ashikaga would decline. The Onin War and the Sengoku period would follow. And the dream of a shogun-turned-emperor would remain just that — a dream.

❦

|

David is an American teacher and translator lost in Japan, trying to capture the beauty of this country one photo at a time and searching for the perfect haiku. He blogs here and at laspina.org. Write him on Mastodon. |

Too band that day didn't work out so well for him. It has been pretty good to me over the years... It's always a bit sad when someone who has the potential to shift paradigms is taken before they get the chance.

What a brilliant piece of historical storytelling 👏

You really sparked our imagination with what could have been if Yoshimitsu had lived a few more years.